I wonder whether the apparent randomness of topics in his essay, as well as the “noise” introduced by his spelling mistakes and typographical errors, are fragments of his own attempt to splice together a viral text. How much of his writing is meant as just social disruption?

Monday, October 27, 2008

I wonder whether the apparent randomness of topics in his essay, as well as the “noise” introduced by his spelling mistakes and typographical errors, are fragments of his own attempt to splice together a viral text. How much of his writing is meant as just social disruption?

Sunday, October 26, 2008

The technological default of race

This coding practice of language, explored by both authors assigned for this week, is applied differently by both. I will focus on Burrough's use, since it pertains to use of technology as traditionally understood--a mechanical and/or electrical apparatus. There is a given availability to technology in Burrough's populist text: "No, 'They' [the users of this technology] are not God or super technicians from outer space. Just technicians operating with well-known equipment and using techniques that can be duplicated by anyone else who can buy and operate the equipment." (p. 25) He argues for an availability of technology to the masses, but this is the only true mention of any class consideration in the text itself (with the major exception of those in power as a class versus the subjugated people). To be able to afford and use the technology is given, and the appeal to the readership of the text to try out these experiments which "any numer can play" further enforces this point.

However, throughout the rest of the text the class argument is made through the assumption of ideas about race. On page 9 the appeal is to the "white race" as the target audience of language-as-virus. The mythology of the Garden of Eden "was a white myth." Growing off of this, Burroughs states that "this leads us to the supposition that the word virus assumed a specifically malignant and lethal form in the white race... the virus stirs uneasily in all your white throats." "Whiteness," defined by Burroughs, is given to be the technological default of race and race relations. This stems from a post-colonial theory and history. It is the white man who is the creator and subject of technology, and is the one constantly represented by this technology (white faces on TV, in positions of power, talking about their expertise, broadcasting it to "white" audiences). This is implicit in the history of the photography of racial types, where the images of a certain individual came to be representative of an entire race, and were used to establish hierarchies of race (race and its aesthetics, assembled in a linear devolution from the Caucasian to the African to the ape). This history cannot be escaped or theorized away, contributable to the power of the written language, which Burroughs points out. Scrambling as a revolutionary technique also has the dangerous consequence of eradicating difference: "Everybody doing it, they all scramble in together and the populations of the earth just settle down in a nice even brown colour. Scrambles is the democratic way, the way of full cellular representation. Scrambles is the American way" (p. 36).

What happens when the subaltern appropriates "white" technology? Do they scramble their "difference" (non-whiteness) with the technological default? Is there a (Third) World Wide Web? Is there a revolutionary potential to technology that applies equally to all "races," or is there an inherent danger to non-white "races" that does not exist for the "white man?"

scrambling, entropy, and exploding systems of control

In response to Meg’s passage about infected identities, that is, language as identity infected by power systems, I considered how Burroughs would respond to Fanon’s problem with language, that of submitting to the language of the oppressor, and that the power of language denies space for other identities. Burroughs suggests scrambling language in order to rail against and explode the power system. I’m not sure how well this idea applies to Fanon’s problem, because the use of creole does not lessen the French language’s power status, although it does allow for the emergence of other identities.

What I find interesting in language-scrambling is the loss of self; a loss of the distinction between sender and receiver into a big scrambled mess: “Everybody doing it, they all scramble in together and the populations of the earth just settle down a nice even brown color.”(36) He calls this “the way of full cellular representation.” ‘Scrambling in together’ thus destroys the system of repression because it singularizes while at the same time destroys the self/other binary, because ‘the other’ is the same as ‘the self’ in its one-ness. It degenerates into entropy, the devolution towards a chaos rendering everything indistinguishable from anything else.

I was confused by scrambling, however, because while it questions the agency of a receiver in deciphering the message (thus the system of control that can then be coopted by revolutionaries), does it assert the authority and power of the sender or does it suggest that the system of control lies in an external actor, context, that scrambles the message between sender and receiver?

The receiver gets a scrambled message, and has to descramble it, depending on his ability. But is the message scrambled by the sender, or is it only scrambled in transmission? In which case, is this scrambling a tool of the sender or an external force (context)? In other words, where does the power of language reside?

His proposed scrambling tests remind me of the Turing test’s effort to determine the ability of the players to establish the correct source of a message. Turing wanted to point out that people cannot fully descramble a message, or they would be able to tell which was computer and which was human (or male or female). Is it the cleverness of the other players that confuse the message, or the context, that of physical separation?

A Mask on a Man, a Man in a Mask

Fanon also sees the more violent side of fragmenting language. Both he and Burroughs speak of the body being penetrated, violated by some oppressing force. But this is a dual attack: for Fanon, the black man is also covered up with a mask even as his body is invaded, dismantled, "scientified;" for Burroughs, the virus has its external component (the screen, the collage) as well as its internal one (the virus already incorporated into us, sometimes latent). For both writers, there is an ambiguity, a slippage between inside and outside in which everything seems to turn inside out, or at least reveals a dual layer: the "Negro" in Europe becomes the European in the Antilles.

There's an odd sense in which putting on the mask of whiteness is the same process, from an inverted perspective, as the other penetrating the same; he is inside the mask and thus gains the power of subversion in the same stroke that he is oppressed. Derrida approaches the language problem from inside of, dare I say it, the dominant discourse. Thus, his solution is a kind of exposure, an opening up of an insular context to a third, external term. Fanon, who approaches from the margins, perhaps even feels thinkers like Derrida co-opting his space, using his alterity to pierce the social membrane or to expose an otherness already within the mask.

The doctor who speaks to the black man in pidgin (the language of the other) traps the other as the other within society. Similarly, "well-meaning" whites, like Sartre, seem to have the same effect when they speak of using the language of the other to liberate all of society. When the other is "brought in" as an external, internalizing force, he is "overdetermined from the outside." What of his own inside, then? The black man needs space, breath, a reprieve from being forced into the political arena.

If I knew Chinese then I could consider better what Burroughs had to say about that...

This linguistic violence manifests itself in a different fashion in Fanon where the use of language is symbolic, powerful, overdeterminate, and negating. That is, the language of the colonized and the language of the colonizer must play and dance in the psychology of the colonized in a peculiar way. The two languages become classist determinants over top of race that must negate biology. What I mean is that in Fanon, Creole is marked, it is dirty. To move up in life means to learn French, the tongue of the colonist; but not just that, it means to become the colonist, to become French, to become European, to become white. In the dealings described by Fanon of the white man with the black man of the Arab, there is always a talking down. There is an assumption from the white man that this person must be uneducated, poor, and, in any case, not a good French speaker and when the response is in good French, the next thought must be that this person is in fact, not truly black; he has mastered our tongue, he is becoming white. The language of the colonizer, and its relation to the native tongue, is, therefore, always coloring the relations and dealings of people but especially of the black person because he is made conscious of it every moment for every utterance must prove and justify his honorary acceptance in the white club; an acceptance forever provisional and with the condition that it may be revoked at any time without notice. A slip of Creole here and you’re done for. The existence illustrated by Fanon (and that which he believes must be rectified) is one of an always already determined from without being constantly engaging with others through willful negation against this foisted upon determination. And this is all made and done through the use and the play of language(s).

If language is violent then it appears so is everything else. Burroughs describes the power relations and assumptions that are implicit in language and, in particular, in the to be verb which frame us and our worldview. In this sense, these ideas have a kinship with the ideas of anarcho-primitivism which views society, and especially technology, as something that is doomed to be oppressive and starts its critique with language and with the technological advancement of agriculture and domestication of livestock which involves the Othering of nature so as to subjugate it. This Othering which becomes ubiquitous and obsessive in control that later manifests itself through slavery and industrialization.

"Other Opinions"

Also, the tape scramblings and playbacks might be called art or experimentation, but they're not science. It doesn't even sound like other than a passing reference to the Law of Averages that Burroughs even looked at basic statistics when considering his field "research." All of that is fine; it can still be an interesting argument, but why he brings viruses into it at all still escapes and bothers me. Spiraling prose that seems like it should (but I do not find to actually) complement his argument, and leaps in causality and possible mathematical ignorance are enough to disgust me away from the text (which means I'm actually fairly happy that we will be discussing it in class because I don't like thinking that about really any text at all, and discussions have sometimes in the past led to a complete change in heart and mind. Already as I work through the text yet again I see passages specific about viruses that I'd like to look at more).

This is all strange for me to begin with, because in reading semiotics I tend to err very much on the side of little narratives, which my truth-value/scientific proof problems with Burroughs obviously do not reflect. But ultimately I just feel like Burroughs gains nothing and loses credibility by his poorly supported although trendy sounding virus thesis.

The comparison to G-d-like power that I mentioned earlier reminds me that I do like his hypothetical three tape-recorder arrangements, in particular the one in which G-d is the third recorder, so that G-d is basically reduced to or at least considered caused by one's feelings of shame and self-conscienceness. Indeed he says the third tape "is objective reality produced by the virus in the host" (10), so G-d is kind of a byproduct of innate ethics and their effects.

As to Fanon... well I'm less opinionated, at least. The structure he's examining as at work in the racial difference is I think very interesting, because it is not merely Otherness, not quite like Ideology, not simply Master-Slave.* One particular section I'd like to look at is on page 133, the paragraphs beginning "But that does not prevent" and "When I read that page." It seems to me here that what he's saying is that he wants racial difference to remain, just not racial hierarchy. Differance, multiplicity, perhaps? Except maybe not simply, because of the overdetermined from the inside and out nature of what he's talking about.

* - Marginally entertaining marginal comment... footnote #24 on page 138 mentions white man as "master," which is from where I took this structure. Interesting self-observation is that I can never think of "master-slave" without thinking of the RS flip-flop circuit in computer hardware. I have since learned that "master-slave" is a common moniker for the latch (although they never told us that in CS0310), but my first exposure to it was as the first page of our very own professor's "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge!" This I note here and call marginally entertaining (if not marginal) because this kind of random overlay of information enters in Burroughs's argument, and is something that I would consider useful in looking at what his view of information outright is.

Burroughs' methods

To unpack my perspective of his writing a little: I see his underlying method as modification of information about the past or the remote. This springs from the observation that we have a small sphere of perception as finite physically rooted organisms and that the expansion of that sphere requires technology. Burroughs knew that most people never saw presidential candidates speak, never saw another continent, never heard the news, without it being digested, transmitted, and excreted at a distance by a media monster. The channel of absorption in which he chose to intervene was that of audio and video, and he believed that by changing the networks of reference between subjects he could alter the way reality really Was.

Today we have the internet, which ought to have changed everything. No longer is our information mediated by corporations, but rather by our equals, our neighbors. Governments and corporations have, in fact, run into trouble because of emergent phenomena beyond their control growing on the internet. So why does Burroughs' message still ring true? Why, upon reading about his methods, does one still see a space -- a constructed reality in need of a revamp -- in which they could be deployed?

I believe that the internet has made the modification of reality through media intervention impossible. While things took a little re-equilibrating after the advent of the internet, the essential state of human perception-at-a-distance has not changed. For example: to know what was happening during the presidential debates I did not read liveblogged accounts of them posted by audience members; I watched CNN and read the New York Times analysis simultaneously. Tomorrow I will not read about the financial crisis on an individual's blog; at best I might read the Huffington Post. For poll results I will visit Intrade, 538, and RealClearPolitics. None of these are run by individuals, and each of these has a brand which could be recognizably parodied, imitated, or otherwise intervened in in the manner Burroughs suggests. But in order to see anything on the internet, you have to want to see it.

And the difficulty with people only seeing what they want to see is that it makes changing preexisting notions of reality even harder than it was for the ideological revolutionary, the advertiser, the dadaist, the missionary, the convicted innocent. Burroughs believed that simply exposing reality to an alternative narrative, however disconnected from it, would affect a change in it. But today, the internet acts as a resonator for the aggregate perception which constructs reality.

So the old media remains strong. Tomorrow thousands of thousands of thousands will read what writers for the New York Times believe to be true. Burroughs with his tape recorders will be lost in the noise of people yelling their beliefs back to themselves. And above it all, unchanged, billions will turn on their television sets and watch anchormen construct state-sanctioned credibility and liveness and the people will believe the commercials and take their new beliefs back to their computers, where they will confirm themselves, where the network of them will confirm them.

The internet made social change seem easy. But cutting through the noise still requires subversion, just of a new kind.

Determining the Body, Resisting Cultural Hegemony

“To stay present…A boy masturbates in front of sex pictures…Cut to face of white man who is burning off black genitals with blow torch” (Burroughs 46)

“To stay absent…Sex phantasies of the boy…The black slumps dead with genitals burned off and intestines popping out.” (Burroughs 46)

Juxtaposing images of a young boy masturbating with images of a white man brutally lynching a black man, Burroughs’ evocative scrambling technique highlights the fetishization of the black body in media and popular culture. Burroughs’ frightening depiction of the bodily results from his splicing and scrambling of sexual imagery and racialized bodies into a cacophony of disgusting yet intriguing imagery. The meanings of the black body are fixed by rigid cultural norms governing race relations and the history of black bodies in relation to white aggressors. In Burroughs’ schema of the reactive mind (RM), seemingly harmless commands such as “to be animals” and “to be a body” become problematic, possessing what Borough’s calls “the most horrific consequences.” Inhabiting a black body, in this schema, may possess the most horrific of these “most horrific consequences,” for the black body is and has been so often reduced to an object of control or possession. While perhaps not an explicit discussion of the meanings of the black body and the embodiment of language within it, Burroughs’ cut-up narrative is full of traces of what Fanon terms the “crushing objecthood” imposed upon those marked by black skin.

Fanon, writing what is in its own way a “cut-up” or scrambled narrative (characterized by extensive citationality and external references), underscores the bodily nature of blackness and the “consciousness of the body” with which the black man is perpetually saddled. (“Fact” 110) The black man’s inability to define himself except in relation to whiteness feeds into the “crushing objecthood” by which “every ontology is made unattainable.” (“Fact” 109) Just as Burroughs’ depiction of a fetishized lyching of a black man shows the determination of blackness through white eyes, Fanon describes how black people, in contrast with jews (an interesting comparison worthy of more critical interrogation), are “overdetermined from without,” their meaning and existence “fixed” by the powerful white elite constituting society’s apparatus of control. (“Fact” 116)

Where Fanon and Burroughs seem to agree—or at least overlap—on the determination of blackness through white-dominated media culture and discursive relations, they differ in their choice of tactics by which to throw off this yoke of oppression. Fanon, whose “only weapon is reason,” becomes frustrated and neurotic by his continual contact with the “unreason” of racism and white oppression. (“Fact” 118). Burroughs, on the other hand, proposes a subversion of reason and order—the cutting up and splicing of language and reality—as the means of subverting the entrenched language systems which govern our experience of reality. Instead of using reason as a weapon, Burroughs effectively inverts reason, cause and effect, and rational speech patterns to create new forms of resistance to dominant cultural hegemony.

While at the time a fringe proposition, it seems that Burroughs’ attention towards processes of cutting, splicing, and reconstitution media such as sound and video has had huge impacts on the development of new media forms and the opening of new sites of resistance to hegemonic systems of power and oppression. Surely that is something that both Burroughs and Fanon could celebrate.

Fanon's Cut-Up

The Fanon MixTape

The first day of my intro Linguistics class we learn to value the spoken word over the written word (there are languages with no written transcription), I've read about the Old Testament as passed down for years and years over a vast land area before a written transcription became available, and language does not need the vocal tract caused by the ancient virus Burroughs references (we have sign language, don't we?). Once I stopped taking Burroughs literally, and opened up to a broader interpretation of his writing, things began to click.

I will look at the three tape recorders he talks about.

We arrive at the initial example on page 10.

#1 is the object we wish to effect (Adam, errors of the senator, pristine Moka Bar)

#2 is access material from tape #1, or the material tape recorder #3 will use to effect tape recorder #1 (Eve, the senator's sexual activity, the surrounding Moka Bar)

#3 "is the objective reality produced by the virus in the host" thus God, the controller, or the operator of power.

Thus, we take the notion of tape recorder, and can apply that to any sort of language/sign/picture/word/audio sound/message we want. As an example of the race situation Fanon speaks of in "The Negro and Language," we could put Fanon in tape recorder 1, Fanon speaking pidgin and then eliete French in tape recorder 2, and the audio conversation from the racist drunk in the bar in tape recorder 3.

Playback or repetition from recorder 3 causes reality to come out from the "reality" on the tape recorder. The reality we have is of Fanon being the "host" for the virus of the French language, a reality which construes Fanon only as the Other within society.

But Burroughs uses the example of tape recorders becuase it allows one to fight back (tape recorders are a realtively inexpensive, democratized technology). He fights back against the Moka Bar, and he urges us to fight back against mass media and the police state by making our own wild mixes (by breaking up "lines of association" (21)).

I guess I have two questions from this scenario.

A. We always see utopian ideals when it comes to technological idealism (a la Enzensberger), but is Burroughs hitting at something beyond the mere technological aspect of the virus/the 3 tape recorders? I don't think YouTube was what he was looking for, so why didn't what he wanted to happen in all of his experiements actually happen?

2. How would it be best to change the Fanon + three tape recorders scenario layed out above? Which aspect of his essay fits each tape recorder?

Other questions:

1. How close is scrambling to noise or encryption (23)? It seems like he is emphasing syntax does not matter with the sign/word/photo/image, some sort of semantic meaning always gets across (in his discussion of subliminal messages). An example of this would be the theoretical alternative "cut-up" press on page 22.

2. Does the "re-interpretation" of scrambled messages hand over the agency of a message to the receiver (24)? How would this "self-ascribed" message play into Fanon's white mask (where a scrambled message "forces something on the subject against his will" (32))?

3. Do we have a new riff on cybernetics by equating language with a biological virus? Do words have control over bodies (e.g., the dicussion of Hubbard's pain producing engrams on 39)? Are we moving too fast when we say that language causes physical effects (such as when Fanon wishes to measure "the modifications of body fluids taht occur in Negros when they arrive in France (Fanon, 22)).

4. I see Burroughs's proposal for a new language as the elimination of identidy. Viruses/tapes control us by giving us an identidy and changing that identidy's reality; such as Fanon's identity giving Creol language or broken French. Fanon wishes to identify the virus and not try to "compete" in a lose-lose situation where the Other is always giving the losing hand identidy (Fanon 28,29). Am I right in thinking that these are the two articles modes of resistance, and if not, what am I missing here? The language virus strangled the ancient humans and labeld him a host, the white attacker tried to strangle Fanon and labeled him as a cultureless foreigner. But both persons must remember they are more than labels: "to the mechanical problem of respiration it must be unsound to gaft a psychological element, the impossibility of expansion" (Fanon, 28).

Infected Identities?

The readings this week discussed how identity is constructed through language. Fanon writes “To speak means to be in a position to use a certain syntax, to grasp the morphology of this or that language, but it means above all to assume a culture, to support the weight of civilization” (17-18, The Negro and Language). Participation in language is participation with the dominant social group. His problematic in The Negro and Language is the specific case of the Negro of Antilles learning French in order to be part of the white world. “Mastery of language affords remarkable power” (18). This “power of language” (39) is problematic for Fanon because it denies a space for other (17) identities.

In relations to Burroughs text, the “power of language” is complicated by his argument that western language has virus-like structures and characteristics. This construction is produced through the falsifications of the syllabic western language: the use of THE, EITHER/OR, and TO BE. These falsifications create the virus which is our notions of identity, “the IS of Identity” (54). Identity is defined clearly by what one is not or by information on a passport.

However, it is “the other” within these texts who is called to use voice and speech as a weapon against a repressive system, to explode and erupt it. This erosive, breaking apart of the system is ending the war game, as Burroughs calls it. But what lies on the other side? If the written word acted as a virus to create the spoken word, then how does the virus go away? Do we lose language and identity, opening up new languages and identities? What marks or damage will the virus leave on a system?

the word made flesh

Virus, Language, Race

According to Burroughs, a virus

- mutated the structure of the (male ape) host's throat, but is passed to his female mate in a sexual frenzy that results from the virus, and this throat continues to exist as part of the structure for posterity,

- (unproblematically) produced the "yellow races"

Whiteness appears (in my reading) to be implicitly aligned with unity and the absolute in Burroughs' text, yet never explicitly treated. In "The Negro and Language," Fanon describes speaking of French by black men as being essential to social status in a colonial structure. "To express it in genetic terms, his phenotype undergoes a definitive, an absolute mutation" (19). What might be the implications of such a mutation, or of mutation in general? How does this scientific analogy play into questions of pattern and transmission that we have discussed before?

A Network of Reference and Implications: Electronic Revolution & its Peers

When I think over, there is a bizarre erasure (or perhaps it is a more naive overlooking) in the Burroughs text, in regard to the 'guerrila media,' and this is the nature of the devices used for capturing, playing back, and editting tape. As proprietary objects, how does Burroughs feel he can subvert order using the same devices order uses to propigate itself? Are not the technologies involved in the undermining of politics also the means by which that politics is maintained? So is Burroughs simply substituting?

Here, it would probably good to interrogate Burroughs' emphasis on "scrambling," on the intense, disorienting, recombination of recorded mediums. Is this a radical discourse? What exactly does Burrough's believe it achieves? And what do you do when commercial media recuperates the scrambling (such as MTV's "switching channels" aesthetics of the 1980's, or high speed montage of commercial film that has become so mainstream that it is a naturalized filmic device)? Has Burrough's recombiant spirit been so absorbed by culture (in musical mash-ups or remixes, or youtube parodies) that it can no longer show culture a new part of itself?

Snow Crash & Electronic Revolution

Perhaps more interesting is the idea of the virus and the belief that the virus through words might actually have a more direct physical impact that society typically gives it credit for. While Burrough's was describing how "scrambled words and tape act like a virus in that they force something on the subject against his will" (Burroughs 32), I could not shake the eerie connection of Burrough's idea to the concept of the "me" and "nam-shub" of Neal Stephenson's "Snow Crash." In that text, Neal Stephenson employs the idea of code-mediated viruses that effect human hackers, and not necessarily their computer hosts. These viruses, are related to Sumerian mythology, where the "me" is a sort of human software, actually programming them to execute certain tasks. The success of these programs was predicated on the existence of the Sumerian language, which essentially worked like a common operating system through which "me" were compiled and executed. The "nam-shub" is a sort of anti-virus, which caused people to forget Sumerian and thus become free from being human-computer slaves. The fascinating thing about the comparison between Snow Crash and Electronic Revolution is that the virus is the danger of the former, and the promising subversive liberator of the latter. However, at one point, Snow Crash's protagonist wonders like Burroughs does, about the origins and meanings of the idea of a virus: "I wonder if viruses have always been with us, or not. There's sort of an implicit assumption that they have been around forever. But maybe that's not true..." (Stephenson 233).

Does it matter? It seems to matter to Burroughs, who not only acknowledges von Steinplatz's theory of the origin of spoken langauge (Burroughs 8) but also wonders if he can "write a passage that will make someone physically ill" with the emphasis on the idea of the written effecting physicality(Burroughs 39). Like the Christian-Right villain of "Snow Crash," Burroughs believes "a far-reaching biologic weapon can be forged from ... language" (53). And it's at that point if not sooner, that we as readers suddenly must confront the violence and power that has been at work throughout not only Burroughs' writing but everything we've read. Is language an operating system and the texts merely programs as in "Snow Crash"? Or have we been wounded and indoctrinated at the hands of fascists like Burroughs, who at least, near the end, has the decency to reveal what's been happening to us.

scrambles is the american way

But not only that, I think that the text in written form also performs some of the scrambling that he repeatedly calls for. Right off the bat, I found that the fact that the text has already been marked up by a previous reader had the effect of thought control. On page 7, I found myself wondering how mitochondria could be viruses that wouldn’t “necessarily be recognized as a virus.” This seems to me like a small scale version of how “riot sound effects can produce an actual riot in a riot situation” (20).

The ideas for action that Burroughs presents also recall the talk by Erkki Huhtamo this past week. Huhtamo argued against accepting Jonathan Crary’s claim that the screen is the “detachment of an image from a larger background,” especially in pre-cinematic media because attractions such as magic lanterns were often presented in public spaces where the external noise of a fairground was never separated from the image. That argument intersects with Burroughs’ ideas for guerilla scrambling at demonstrations. External playback and cut-up tape recording interact with the people, “continually subject to random juxtaposition” (21). In any case, Burroughs numerous suggestions were a very fruitful read in the week before we have our presentations.

Thursday, October 23, 2008

semiotics student seeking group!

Some of the general and recurrent ideas about which I love reading include schizophrenia-as-metaphor, bricolage, and little narratives, which have come up in the readings in conjunction with information studies. More specifically to this class I'm quite interested in the disembodiment of information (from its material form), and then in its fallout the notions of disembodiment, bodies, information, and power that are discussed by many of the authors we've read. I've become very alert to and fascinated by juxtapositions with capitalism, although I think that would perhaps better be suited to a more general and theoretical study and possibly less to this particular project.

Many of the specific ideas I was looking at involved either (1) analyses of the structure and characteristics of the World Wide Web (or more narrowly of Google/Wikipedia/&c. as its heralds), or (2) juxtapositions/comparisons with print media arts... but even here, there are some ideas that attract me more for which I just could not come up with a particular object or referent, so I'm quite open.

Which authors are tied into the project is highly dependent for me on the topic, and I'd be happy with most. I found Hayles especially rich; also Plant, Derrida as usual, and the Von Foerster, actually.

Please let me know by comment here or e-mail (Jenny_Filipetti@brown.edu) if you share some similar general interests, and we could meet sometime in the next couple days to start thinking through specific ideas!

Monday, October 20, 2008

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Cartography

What constitutes for me this difference between cartography and artitechture is the place in which objects and subjects become situated within their particular structures and non-structures. An architectural genealogy would build, for an example, a house out of constituent elements. In the case of discpline, we would have the state, the laws, the penal system, and all that stuff. For a proper functioning house so to speak we would need all these elements in a specific combination. Once all these elements come together then we can analyze the structure as such. But, to extend the metaphor just one step further, we can only engage in the house as structure, by going through the front door and looking around.

Cartography precisely contrasts with this structural view. If Deleuze is correct, Foucault is precisely not building any sort of edifice. Rather, cartography is a kind of topographical imaging of elements that have no fixed places. Thus, topographical multiplicity is a geneaology of relational points that contribute to a mapping. When Delueze describes Foucault's Discpline and Punish, what becomes important is the relation of differening elements such as prisons, laws, states rather then their particular structural places. Additionally, it seems that these relationships are always shifting, simutanously working and being worked on by the mapping they produce. This in effect creates a cartography of discipline, or biopower, or govermentality, or whatever else.

Then new developements such as technology get placed into this cartography. Deleuze says that" Technology is therefore social before it is technical." I think it is interesting in the vein of Deleuze to think about how emerging technologies fit into the sort of Foucauldian assemblege that he describes. From an edificial viewpoint this would mimic already existing structural elements under the names of confession, servilliance, or power. I think that what Deleuze is saying is that from a Cartography emerging technologies can only be analysed through comparison in very superficial ways. What really happens is that emerging relational apparatus alter the very social mapping. This in effect would transmute Foucauldian cartographies.

No relationship at all

Again, even keeping in mind that “Signature, Event, Context” is a seminal piece of work on semiotics, I can’t help but wonder if Derrida is laughing at us behind this screen of absence-nonpresence-possiblepresence(?) words and meanings.

In any case, despite an incredible attempt to hide his point in clutters of ivory-tower language, I thought Derrida’s point in this phrase was quite interesting (once I managed to unpack it). He seems to be pointing out that we can’t view linguistic communication simply as a metaphor for oral or physical communication because that would assume that the metaphor is itself a form of communication. However, because there is still a subjective shakiness in bridging the gap between the metaphorical and literal context of a word, we cannot just assume that such metaphor is concrete and defined.

For me, this raises interesting points on Derrida’s later arguments/examples on the “iterability” of the sign. Obviously, the written word can be placed in any context, giving it whatever new meaning the author so chooses- this is something Derrida points out when he writes, “every sign, linguistic or nonlinguistic, spoken or written . . . can be cited, put in quotation marks; in so doing it can break with every given context, engendering an infinity of new contexts in a manner which is absolutely illimitable.”

It seems then that it is not simply an arbitrary relationship that the signifier has with the signified, but simply no relationship at all. If the bridge between metaphor and literal, even the pure citation of text, is so tenuous and shaky as to have an infinite set of meanings…well, instead of a bridge that just seems like a hole to me. A hole that can be filled with whatever we choose to do with it.

Which is maybe what I just did with my quote.

Statements

"[A] science never absorbs the family or formation which defines it; the scientific status and pretensions of psychiatry cannot quell juridical texts, literary expressions, philosophical reflections, political decisions and public opinions, which all form and integral part of the corresponding formation" (19).

What this seems to imply in addition to history's nonlinearity is its undividability. To study economic history without studying political history, natural history, and cultural history is in a sense to lose important parts of the topic that is being considered and when the topic is something like power, it's expression comes in many forms.

All this appears as a complement to Derrida's deconstruction of language, his emphasis on the text as being conditioned by absence while representing a past presence and his consideration of the performative citation.

I'll answer: "Perhaps."

Derrida does not wish to negate, to sew confusion and undermine meaning. Rather, he wishes to make room for the deferred, the multiplicitous, the other, within the previously closed system. He makes room at the very heart of it, founding rationality and consensus upon those very substitutions and mutations that once terrified: the supplemental. In so doing, he avoids the trap of reifying an "absence" that merely buttresses a "present." Derrida's is the absence of differance, of endless but productive difference and deferral.

Derrida does not deny performativity or the specificity of communicative acts. I think he is simply reacting to the danger inherent in a community that believes in the transparency of its intentions, the unity of its goals, the cleanness of its contact. The notion of writing/signature offers an escape route between the constraining walls of author and reader, though the third term is never clear. Perhaps this third must always be blurry, in motion, potential. I still find it difficult to wrap my mind around the "legibility" of a coded piece of writing whose coders no longer exist (or have never existed). But it feels necessary.

Signing off. Eli.

presence/absence/source

Addressing these two accouts, Derrida writes: "By definition, a written signature implies the actual or empirical nonpresence of the signer."

I am particularly interested in Derrida's selection of the word "nonpresence" as opposed to the more conventional choice of "absence." What is the difference between nonpresence and absence? Is nonpresence marked by a "trace" of the once-presentness of the author, while absence is devoid of this trace? Does the written signature constitute this trace? There is no doubt in my mind that Derrida chose this word very specifically and intentionally, yet I can't establish why exactly that is.

Perhaps it has something to do with the notion of "source" as treated by Austin, specifically the idea that a signature indicates the "presence" of the source of communication in the written word. It is clear that the source of an oral utterance must be present to the utterance, but I find problematic Austin's assertion that "appending a signature" to a written utterance constitutes the "presence" of the source of the utterance.

The emergence of new media is creating huge problems for such notions of presence and source, because the rise of open source languages and remote internet discourses is turning inside-out our cultural and philosophical understandings of self, agency, and individuality. As meg mentioned in her discussion of email signatures, the validity of a signature is no longer predicated on“the pure reproducibility of a pure event.” We live in an era of automated payroll machines that print out 50000 "signed" cheques every other friday, cheques that, to a bank, are no different than a cheque signed by an individual in a discreet, purely reproducable event. We update blogs and databases such as wikipedia which, until a few years ago, never required "sources" to "sign" their contributions with a username or ip address.

In light of these technologies and new forms of discourse, it seems like we need a revision of the notion of signature as a singularly reproducable pure event. As we log onto the web and visit websites, post on blogs, and share information, we are silently and unknowingly leaving signatures of our momentary presence at each of the virtual spaces we visit. In this instance, I am reminded of the student in Alabama who hacked Sarah Palin's email account, probably assuming he would get away with it. By tracking the "signature" of his IP address and computer information, authorities pinpointed his identity and proved his guilt. How such unintended, automatically-produced virtual signatures come to bear on issues of privacy, neutrality, and surveillance will play out in the very near future on our cultural and virtual landscapes.

understanding and ownership

Derrida's and Foucault's opposite approaches

On the other hand, in Signature, Event, Context, Derrida tries to demonstrate the essential independence of concepts or utterances and their removal from the people who originate them. I’ve only got a sliver of an idea why he wants to perform this operation of absolute reduction and isolation (and I am sure he has an agenda). But at the end of his piece he summarizes several inversions he has executed: First, that “writing” is “not the means of transference of meaning” but a “historical expansion of a general writing” which includes consciousness among its consequences—in other words, writing is not the product of the author but the other way around. Second, that writing is not the locus of meaning but rather that which is read. Third, that all oppositions of metaphysical concepts constitute a hierarchy which may be disturbed through an operation of identification and inversion called “deconstruction”

While Foucault is searching for truth in modernity, a quest which necessarily involves the disentanglement of contradictory concepts, he maintains an approach grounded in the aesthetic or holistic. Las Meninas is centered on a text designed with aesthetic perception in mind which also happens to constitute a locus of Classical thought. He also explicitly tries to decode “the Same,” an extremely inclusive topic. Derrida, on the other hand, tries to disentangle the same culture with a divisive, quantum approach. Rather than trying to understand culture as a whole Derrida looks for wedges he can strengthen between people and words.

I’ve struggled to understand why he does this when another esteemed philosopher takes a diametrically opposed approach. My conclusions so far are that both are trying to tie everything together. Foucault is willing to deal with the uncertainty of a large field of view. Derrida, uncomfortable with the lapse in “rigor” that approach necessitates, prefers to split and divide all concepts, thus leveling the structures of thought to rubble and building them anew. But he neglects the aesthetic or holistic point of view. Operating strictly on ideas tends to introduce strange inconsistencies with reality, and Derrida’s approach is no exception…

half-witted commentary

Foucault’s terms: “system”/“system of elements” (x, xx), “positive unconscious” (xi), “rules of discourse” (xiv), “order” (xx), “codes of culture” (xx), “episteme” (xxii)

Derrida’s terms: “ideology” (6), “logocentrism” (20)

Regardless of the distinctions between each of these concepts, they all contribute to a “theory of discursive practice” (Foucault xiv), which is a major project of (post-)structuralism. The question that Sinje brings up, of how the mapping or displacement of the rules of discourse that both of these texts engage in can open up new spaces, if not outside the order of things then between the categories of its taxonomies, is a persistent one within this discourse.

Foucault's Mirror (Reflexivity in Visuality)

Foucault's "Las Meninas" was a welcome new twist on the ideas of reflexivity that has been traced thus far in the course through N. Catherine Hayles' How We Became Posthuman, as well as in Norbert Weiner's The Human Use of Human Beings. In particular, I found myself coming back to a quote of Hayles',

"Reflexivity entered cybernetics primarily through discussions about the observer... The objectivist view sees information flowing from the system to the observers, but feedback, can also loop through the observers drawing them into become part of the system being observed (Hayles 9).""Drawing" becomes an interesting verbal choice when this statement is considered through Foucault's writing on Las Meninas. Indeed, it seems that Foucault is utterly fixated on this idea of the Velaquez painting as an articulation of reflexivity, and what's more, Foucault's approach, like that of Velazquez smiling within his own painting, seems to be that of the reflexive author, cybernetically unable of distancing himself from his observations. To return to Hayles, "It is only a slight exaggeration to say that contemporary critical theory is produced by the reflexivity that it also produces (an observation that is, of course, also reflexive)" (Hayles 9).

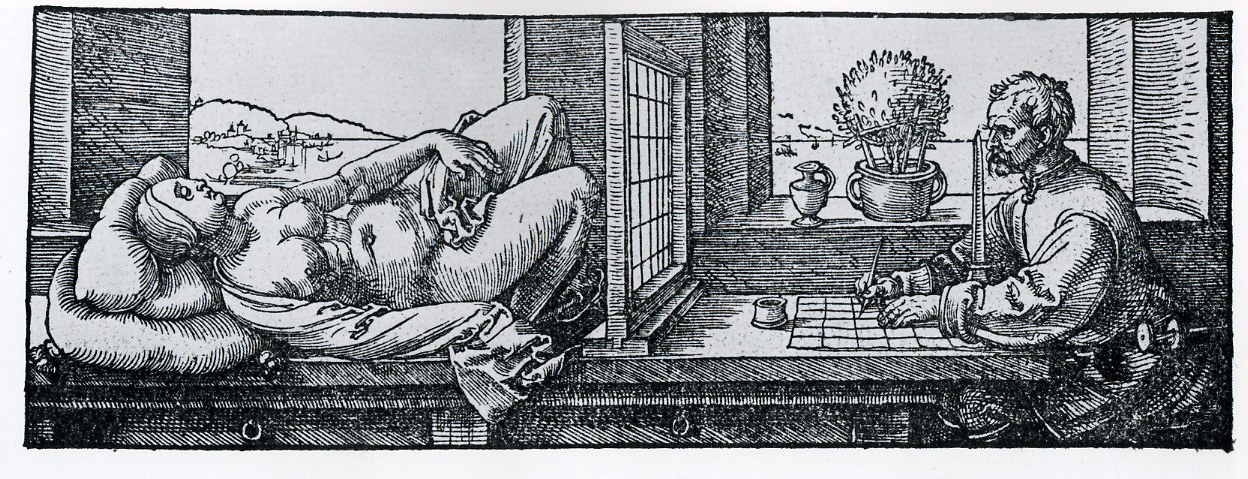

From the Western schema of perspective (shown above in a Durer etching), with unifying vanishing points located at the eye of the observer and in the background of the painting, Foucault points out the inherent reflexivity of "Las Meninas."

From the eyes of the painter to what he is observing there runs a compelling line that we, the onlookers, have no power of evading, it runs through the real picture and emerges from its surface to join the place from which we see the painter observing us... in appearance, this locus is a simple one; a matter of pure reciprocity (Foucault 4).In this visuality, the gaze of "the painter" as well as the perspectival orienation of the painting, situates the observer has not outside the painting, but within it, which is not to say that a material situating takes place, but rather than the construction of the visuality of "Las Meninas" can only take when the viewer enters the necessarily reflexive point of observation. And in that moment, with the connecting line uniting painted subjects and the observing eye (recast from objective external perspective to subjective vision of reciprocal construction), one can understand why "the painter" stands poised with his paint brush and palette eying the observer. His gaze as drawn the observer into the painting. His drawing draws.

So we assess the mirror. A mirror which situates not as what we think we are, but what the painting casts us as, sovereign in perspective, from whom the painting (and its field of vision) is oriented. But it is a paradoxical sense of reflexivity, for though we recognize our engagement (and necessary intrusion) into the visual field of the painting, we recognize that our engagement with it seems to yield no effective way of looking at ourselves. Of establishing who we are to the painting, "Because we can only see that reverse side, we do not know who we are, or what we are doing. Seeing or seen?" (Foucault 5).

And indeed we can never know this other reality. Because to know would really be to nullify our intrusion by quantifying our change to the system. Which is why we endeavor towards contained reflexivities, and why the cybernetics of Norbert Weiner wanted to only allow reflexivity to happen at a quantified depth. Because the mirrors are too many, and the reflections to dynamic, to allow us a empirical look at a world, that does not (perhaps cannot) be measured without remembering to measure ourselves, the eyes that produce the painting but are not the painting themselves.

language in derrida & deleuze

reflexivity and discourse

Understanding Derrida

The absence of which I speak is the absence of the self, which is constructed by language. In the idea of performative utterances (as I understand it, though from the Derrida piece it appears that Austin changed his mind on some points after his better-known work) there is the possibility of the failure of the utterance: to Austin, the performative fails to function if the context is incorrect. However, as Derrida points out, there is no such thing as context.

It seems that there are only two things: there is the self, whether it is named trace, dasein, presence, etc. Then there are other things. Writing is not another thing, because all language is writing, which is more or less the same thing as being, or at any rate one requires the other ("the essential predicates in a minimal determination of the classical concept of writing ... are ... to be found in all language, in spoken language for instance, and ultimately in the totality of 'experience'"), and all attempts at delineating the boundaries of experience, as far as I can tell, have failed. "Communication" is something that takes place within the inaccessible "self," as is "writing," because writing requires reading to truly function as writing, and reading is not an attribute of the material text, but of the immaterial reader. The context of an utterance is ultimately determined by the reader and no one else, hence the intrinsic possibility of the failure of a performative.

For instance: Derrida quotes Austin discussing the situation of the personal signature. For Austin signatures are inherently performative: in a spoken utterance, the word I functions in the same way that a signature does with a written text, it indicates the speaker and allows the recipient of the communique to situate himself in a contextualized situation, validating the utterance as a performative. However, the same slippage that is characteristic of the word I (its meaning is context-specific) applies to the signature: for example, it is entirely possible to falsify a signature, or to simply refuse to acquiesce to its supposed authority. In both of these cases the failure of the performative is caused by the context, but again, the context is simply the absence of the I. To Austin the possibility of this failure is a parasite on language, to Derrida it is the point at which Austins analysis fails.

So there seem to be a few conclusions (though inconclusive ones) to which we are drawn: all writing is language, or all language is writing; regardless of the order of terms, they both refer to a problem, to wit: there is writing, and there are books, but they only exist as such when they are apprehended by a cognizant reader. The problem is that, as I said earlier, "writing" and "reading" are both attributes of the inaccessible subject, but anything that can be demonstrated as writing (a written text, or anything else) is simply an object: in order to be transformed (transsubstantiated) into the function of reading or writing, it requires the supplementary addition of the reader, who grants the object the qualities of existence, otherness, and iterability, though none of these inhere in the object: they are attributes of the subject as object. When I look at the computer screen I am hypothetically "seeing" something real, but really there is only a process I call "myself" or "I," which includes the computer screen: if I see it, and understand it, it is only because I am understanding the way that that piece of myself functions in relation to the other pieces of myself.

So in the last analysis, if I understand correctly, all we can do is continue to exacerbate the différance, spiraling inwards towards a continually inaccessible center. Is that what Derrida's saying? It appears that since Plato, or more recently, since the Cartesian Cogito, people have been trying to situate the subject in an appropriate location (so to speak). The greatest innovation of semiotics, as I understand it, was to propose that the subject should be sought in the (supposedly comprehensible) operation of the dead universe of writing. Derrida is wonderful but maddening, because no matter how hard I try to follow him all I end up with is the Hindu admonition from master to student: neti, neti (not that, not that); an understanding of things as their own negatives. But Derrida mentions occasionally that logical negativity isn't what he's looking for, so I guess I have no idea.

About the dog

This term, "observation-as-spectacle," is intriguing for its use here since it robs what should be the proper spectacle in a painting by a artist in the employ of a royal court, which are the sovereigns themselves. This optics of sovereignty that is subverted places the burden or locus of its effects instead on the painting's audience, or rather on the act of vision performed by said audience. When Foucault asks us to "pretend to not know who is to be reflected in the depths of that mirror," he is asking us to remember that the mirror exists only as an object or actor in one of the potential networks that can be drawn in the painting. The mirror, as much as it appears to reflect the position of the invisible audience, is simply revealing what is or will soon become the side of the canvas we, at first glance, "cannot see." In this way, the painting inhabits this seminal position in Foucault's thought: the painting allows its viewer to be implicated in a new position in regards to her or himself: a blending of subject and object, of the mundane viewer with the sovereign.

Yet when Foucault says that the "pure reciprocity" of the image is uncoupled by the canvas' back and the dog in the lower-right corner, I do not agree. The canvas, acting itself as a boundary object, for all intents and purposes is the image we see on the mirror (a mirror which sits strangely among a wall flush with paintings)--it does not break the continuity of the two scenes constructed for each other. What interests me the most is the dog in the lower right corner, what Foucault claims is solely an "object to be seen." The dog, its head bowed in deference to the invisible they on the other side of the painting it inhabits, and its eyes cast respectfully to the side, acknowledges the non-presence of the viewer as sovereign. It lays out at our feet, at the feet of also the figures in the painting itself. It reinforces the importance of the viewer by interacting with us fully, giving the human as subject of inquiry the respect deserved.

Taxonomy & the tabula

The particular taxonomy Foucault chooses, one of animals appearing in a Chinese encyclopedia appearing in a Borges' story, brings to bear questions of the real and the illusory, the fantastic and the natural, the normal and the monstrous. The quality of monstrosity "would not even be present at all in this classification had it not insinuated itself into the empty space, the interstitial blanks separating all these entities from one another" (xvi). It is in fact the "space" of or for language that then becomes Foucault's concern, for where else would the "propinquity of things listed" be possible but "in the non-place of language?" (xvii). This concern with space or place is related to his having noted in the foreword that this text is a project of archaeology and is to be considered an open "site" : in his story, Borges "does away with the site, the mute ground upon which it is possible for entities to be juxtaposed" (xvii).

The table, or tabula, is this site: the table upon which, since the beginning of time, language has intersected space (xvii). A more concise definition can also be found on xviii. As Foucault continues on to talk about aphasia, and the aphasics failure to group objects together except in "tiny, fragmented regions in which nameless resemblances agglutinate things into unconnected islets," I am reminded of Sadie Plant's discussion of hysteria, the idea of wandering or of women's inability or lack of desire to identify themselves with a metier for their entire lives. I then became interested not only in how these unconnected islets are phrased in an order that keeps unraveling, for lack of any governing semantic order, but also in how this notion of the tabula and of connections between objects in an order can be related to the idea of a network.

"Atopia, aphasia," says Foucault. How does the table relate to, for example, cyberspace, or the disembodied definition of information. Is the internet a "ceremonial space, overburdened with complex figures, with tangled paths, strange places, secret passages, and unexpected communications" (language that recalls to me, again, Zeros and Ones) (xix). What is the pure experience of order, then?

Signatures and Emails

Derrida’s “Signature, Event, Context” is a crucial text for any discussion on communication. My interest with the text was in the end section on signatures because of what it means for signatures in the most prevalent form of written communication today - email. What is the state of the online email signature?

Meg Goetsch

Publicity Director

Brown Student and Community Radio

Bsrlive.com

88.1 fm

There is yet another layer to email that connects to Derrida’s discussion on context. He writes about context as the rupture of a written sign. This open system of writing “one can perhaps come to recognize other possibilities in it by inscribing it or grafting it onto other chains. No context can entirely enclose it. Nor any code, the code here being both the possibility and impossibility of writing, of its essential iterability” (9). An article I read this weekend pointed to email’s “asynchronous” communication, the fact that exchanges do not happen between people in real time. The “delay” between sending and receiving is nearly erased by the marking of the time it was sent. Also with the increase of iphones and blackberries constantly on and connected there is no delay. One begins to assume that when an email is sent it is immediately viewed. With these points in mind what does this mean for the signatures relation to the present - what has happened to the signature-event? What happens to presence when signatures are by nature multiple online? Can there be signatures online?

Monday, October 6, 2008

Narrative (Dis)organization, natural philosophy, the weaving of words

For this reason, Plant’s organizational schema was useful to me, allowing me to better understand her narrative in terms of the references that she used. In addition, the bold terms and quotations served to break the text into more palatable bits, an effect that itself reminded me of the computerization of knowledge and the transformation of books, theories, and equations into streams of informational code, zeroes and ones. While certainly useful and interesting, I found Plant’s organization frustrating in that I found myself at times not understanding either her references themselves or her reasons for invoking them at a specific time. For this reason, I would propose a hypertextual edition of the book, allowing readers to “click through” to each referenced person or work to evaluate the reference in its own context and determine how it comes to bear on Plant’s larger work. With this setup, the work of reading zeroes and ones might be more efficient and effective due to the ease of accessing “linked” information i.e. the bolded captions.

Focusing on the content of the book, I was intrigued by Plant’s weaving of the history of natural philosophy throughout her feminist account of cybernetics. At the time when Charles Babbage was building his adding machine, the word “science” had barely come into play, and Babbage himself was considered as much a “natural philosopher” as an engineer. What are the differences between science, natural philosophy, and engineering, and how do new ideas about cybernetics and computers conform to or call into question these categories?

I also found myself drawn to Plant’s discussion of textiles and the art of weaving, a skill that she equates with technology manufacturing as a site of widespread low-wage female employment. It seems that Plant is herself a weaver of words. Her work, viewed in these terms, can be seen as a complex patchwork of contemporary analysis stitched together by historical, scientific, and cultural themes that allow seamless transition between ideas of old and theory of new, between antiquated forms and new media.

I look forward to discussing how effective this work is, and whether people think that Plant’s organizational schema and unique style of “écriture féminine” are more or less helpful in advancing her ideas and creating questions and textual problems for analysis.